Founders of drug discovery engine companies need to kill four major risks

A second thought piece on the landscape of biotech venture

This blog article serves as background reading for a forthcoming investment thesis. Over the recent years, I have accumulated anecdotes and advice from emerging and seasoned founders and investors. Herein, I discuss the challenges that founders face as they are building drug discovery engine companies. I also describe ideal attributes of a promising and investable founder and their platform company.

Read my initial thought piece on the landscape of biotech venture:

A war between proponents of founder-led and VC-led venture models

Highlights & Takeaways

Platform technologies are a form of leveraged value creation for drug discovery efforts. By pouring resources into building a robust drug discovery engine, later on new products can be quickly derived and advanced toward the clinic. The value of a biotech company is typically tied to the progress of its drug candidates, but sophisticated platforms offer the ability to rapidly expand the therapeutic pipeline and thus generate more value.

Drug discovery startups building platform technologies require incredible amounts of resources, time, and luck. Their founders must be capable of gathering these resources and executing quickly despite facing unknown challenges. Four major risks that founders must address include (1) financing, (2) recruitment and retention, (3) technology development, (4) product-market fit.

Overcoming these major risks are critical for building a robust platform, pipeline, and partnerships (the 3 Ps). It necessitates that founders take an approach involving consensus-driven execution and opportunistic dealmaking. Furthermore, founders should incorporate algorithms, automation, and arbitrage (the 3 As) to be highly efficient and create durable competitive advantages. Here, I will tease the readers about my investment thesis.

Platform technologies offer leveraged value creation

Drug discovery engines, i.e. platform technologies, have tremendous potential for identifying and optimizing drug candidates. Startups with platform technologies can create significant value by generating multiple therapeutic assets or offering a suite of products or services. Moreover, their continued growth is increasingly durable because they can continue to snowball and accumulate more assets, products, and services. Platform development and dataset curation creates a robust and virtuous cycle of value creation. It is leveraged in the sense that spending significant resources on advancing platform capabilities, rather than initial assets, will amplify future value creation if successful. However, failure means that the resources were wasted and the opportunity costs could be catastrophic to the company.

In drug discovery, more value is created as therapeutic assets approach and progress through clinical trials and demonstrate in-human data. Safe and efficacious drug candidates are highly valued. Partnerships with big pharma or other large biotechs are also a useful validation of technological differentiation. However, startups can create pseudo-value through loose demonstration of platform capabilities, or through rapidly advancing suboptimal drug candidates into the clinic. Stacking the board of directors or advisors can also be forms of pseudo-value if these individuals do not actively contribute to the progress of the startup. Drug discovery startups can also exit long before genuinely testing their hypotheses, e.g. IPO or M&A as a preclinical or early-clinical company. All of this is quite detrimental to the biotech sector as a whole, but the reality is that some companies are actually pumped and dumped in this manner. It is vital for the investor to be quite astute and carefully evaluate whether a company has created real value, or has bewitched many other investors with pseudo-value. In this bear market, it is increasingly important to create real value as capital markets tighten and financing risks grow.

Considering all of this, founders need to be capable of raising tremendous amounts of capital (e.g. $1B across 10+ years), building impressive teams (e.g. scientists for animal studies, regulatory affairs specialists, manufacturing experts), advancing the technology (e.g. expand platform capabilities, derive new assets), managing robust business development (e.g. tech transfer, co-discovery and co-development), and accessing the market (e.g. identify appropriate patient population, navigate regulatory processes, organize sale and distribution channels). These risks often go hand-in-hand, for example recruiting and partnerships. Having a strong CSO can direct the preclinical research team toward efficiently producing valuable compound data and get big pharma excited for dealmaking.

Financing risk: thinking in terms of platform, pipeline, and crossover investors

Venture creation firms offer an incredible advantage for their portfolio companies: reliable financing throughout the incubation period. Founders of startups outside of established venture creation firms need to think very carefully about the stages of investments. A paradigm shift from considering “techbio vs biotech” to “platform vs pipeline” needs to be made. I think capital pools in the private markets can be stratified as platform, pipeline, and crossover investors. Platform investors tend to focus on the potential of a given platform technology and can evaluate it in terms of composability and extensibility. However, they may have limited ability to analyze preclinical data, or simply do not consider it as that important. In contrast, pipeline investors tend to focus on the available therapeutic compound data and evaluate its potential to be optimized as a development candidate and brought into the clinic. These investors may underappreciate or completely disregard the platform technology. Crossover investors tend to have an outsized concern about public market conditions and may or may not hold onto their investments after the lock-up period following IPO.

Of course, there are investors that will deploy capital across the whole lifetime of a startup or act as a hybrid of multiple classes, but it is useful to think about this three-class stratification. Founders need to be able to fundraise from all investor classes. This is because building a platform technology and then advancing drug candidates is an extremely expensive endeavor. Some investors may be hybrids or even encompass all attributes, thereby supporting portfolio companies through multiple stages of the biotech startup lifecycle.

Source: DeFeudis 2021

Source: McKinsey report

Venture financing is increasingly robust for platform plays, especially for those that are in the early stages. Platform companies may initially focus on fundraising from platform investors, i.e. venture capitalists that have a predilection to investing in emerging modalities or intriguing technologies that incorporate algorithms or automation. These platform investors may be more tolerant of a startup lacking therapeutic programs. Conversely, pipeline investors expect a robust therapeutic strategy and rationale for indication selection. Some may even require extensive preclinical data. By nature, platform investors tend to invest at earlier stages than pipeline investors. As the company matures and considers IPO’ing as a possible exit, the founder must engage with crossover investors who care a lot about the conditions and sentiment of the public markets. A founder of a drug discovery platform company must be able to transverse investor classes in the early rounds of financing. Value creation must be carefully considered for each financing round, and these considerations will differ between platform investors, pipeline investors, and crossover investors.

Capital raises are extremely important, as an inadequately financed biotech startup will never be able to test their hypotheses due to the lengthy drug discovery and development process. There is a financial “valley of death” that greatly hinders clinical translation of scientific discoveries. This has been solved in part by the existence of venture creation firms. Venture creation firms offer a significant pool of capital to support early-stage biotech companies in building their platform and generating exciting data. They aim to position portfolio companies for subsequent financing by external investors. For example, Third Rock Ventures recently announced a $1.1B fund for creating 10 new portfolio companies (ref; ref). To date, their approach has enabled the regulatory approval and commercialization of 18 products.

Recruitment and retention: sparsely distributed talent and organizational management

Startups are heavily constrained by small talent pools, especially in drug discovery. Over the last decade, Bruce Booth of Atlas Ventures has often shared concerns about a major talent crisis in the biotech sector. Here are highlights from his various blog articles: Extensive academic training is not equivalent to industry experience, and oftentimes startups must acquire talent from big pharma (ref). Startups are inherently resource-limited, so it is difficult to cultivate research capabilities on capital generated from expensive venture financing instead of large profit margins. Furthermore, teamwork is emphasized much more in industry compared to the academic setting. There is significant geographical consolidation of talent, particularly in Boston and the San Francisco Bay Area (ref). Not only do these regions have numerous universities, many pharmaceutical companies are located in Boston and the SF Bay Area. Competition for talent remains intense. Many companies are aggressively utilizing freelance consultants and contract research organizations (CROs) in lieu of hiring more employees (ref; ref). For example, when Gilead acquired Nimbus’ phase 2-ready NASH program, Nimbus had “only” 25 employees and 150+ consultants and collaborating scientists.

Despite the ongoing macroeconomic downturn, executives and senior management roles remain hotly sought after (ref). For companies backed by deep-pocketed investors, management talent is the next major hurdle to overcome. Leadership candidates are demanding increasingly larger equity stakes. These roles include chief executive officer (CEO), chief operating officer (COO), chief scientific officer (CSO), chief medical officer (CMO), chief financial officer (CFO), chief business officer (CBO), head of chemistry, manufacturing and controls (CMC), etc. Such positions are difficult to hire for and challenging to replace. Great people are not fungible, especially for a resource-constrained startup. Recruiters can be helpful, but most of the best employees are likely going to be hired through the network. An equity-heavy compensation package is important, but having mission alignment is absolutely necessary. Job candidates care a lot about the company mission in addition to the compensation. This could have a serious impact on the employee turnover rate.

Sam Altman has an insightful blog article on how to hire. This is worth a close read for any founder with great aspirations!

Technology development: systems engineering principles and toy models

Once a founder is able to secure a financial runway and organize a talented team, the next major hurdle is developing the technology. Technology development is nontrivial and sometimes esoteric. It requires scientists and engineers with deep technical knowledge and capabilities to work together and build something that has never been done before. It is useful to consider technology development in a rigorous and methodical framework. As a physics student in college, I had often studied problems in the context of systems engineering principles and toy models. Studying from the bottom-up is an excellent approach to deeply understanding how things work, and by extension the true value of something.

Through the lens of systems design, we can deeply understand how technologies work and how they can be used most effectively. There are (at least) two fundamental attributes of robust platform technologies: composability and extensibility. Composability is the capacity for a system to have modular components that can be assembled in a variety of ways. Extensibility is the capacity for a system to accumulate new functions and features, whether by addition or modification. An innovation which is composable and extensible can be readily used for robust value creation. For example, Genentech’s molecular cloning was composable and extensible in the sense that synthetic genes could be placed and rearranged in a plasmid, then used to express a multiplicity of non-host proteins. This led to immense value creation, such as treating diabetic patients with human insulin instead of less tolerable, sometimes deadly, animal insulin. Genentech created an impressive and unprecedented partnership with Eli Lilly to manufacture human insulin at scale, which effectively launched the biotech industry and established how business development with big pharma could be done.

Toy models are used in greatly simplifying or eliminating complexity to understand real-world processes. Proof-of-concept experiments conducted with increasingly intricate representations help offer greater confidence that the underlying idea could work in a patient. In the drug discovery process, this could mean proceeding from cell lines to lab animals for evaluating efficacy and toxicity. Even in drug development, clinical trials are usually conducted with very stringent inclusion/exclusion criteria which greatly narrows the participating pool selected from the broader, relevant patient population. Of course, “all models are wrong, but some are useful” and it is up to the investigator to appropriately assess the validity of the experimental results (and whether the experimental design was even reasonable in the first place!). Throughout drug discovery and development, the team should be considering and refining the target product profile (TPP) in the context of the standard of care. Therapeutic candidates should be advanced for a specific indication in a target population with ideal and measurable efficacy and safety profiles. This should make it clear what the value proposition is and how it can be demonstrated in a rigorous clinical trial. A toy model of the TPP would be quite valuable even during preclinical studies to ensure that the early allocation of limited resources is pushing the startup in the right direction.

Product-market fit: needfinding and dealmaking

Figuring out product-market fit is an interesting challenge in drug discovery, even among early-stage ventures. The creation of drugs is an extraordinarily technical and ridiculously expensive endeavor, and tends to be immensely loss-making. Arguably, the demonstration of product-market fit in therapeutics is not tied to revenue generation. Many biotech companies exit via M&A or IPO with virtually no revenue generated to date, and perhaps not even to be expected for several years. This is because, surprisingly, many stakeholders have an extraordinary belief that one day the startup could have therapeutic products that can generate incredible amounts of revenue through addressing unmet needs in the clinic. In some cases, an efficacious drug could offer monopolistic returns where all other drug candidates have completely failed. The sheer potential of any given therapeutics company is what continues to fuel the biotech venture ecosystem. So given the highly speculative nature of drug discovery, value creation can be reasoned as being driven almost entirely by needfinding and dealmaking.

Partnerships are early indicators of product-market fit. The main objective of a partnership is to share resources and capabilities that the other partner does not have or cannot afford. However, partnerships also offer validation for the potential that a novel platform or product(s) could have. A deal worth millions (or billions) of dollars implies that there is an appropriately identified need to be addressed, and that the startup could be the one to solve that unmet need. Partnerships exist in many forms, such as co-discovery/co-development or technology transfer. Usually, there are certain milestones tied to clinical development and sales. Earnout payments are colloquially described as “biobucks”, and usually only a small fraction of milestones are actually achieved (ref; ref).

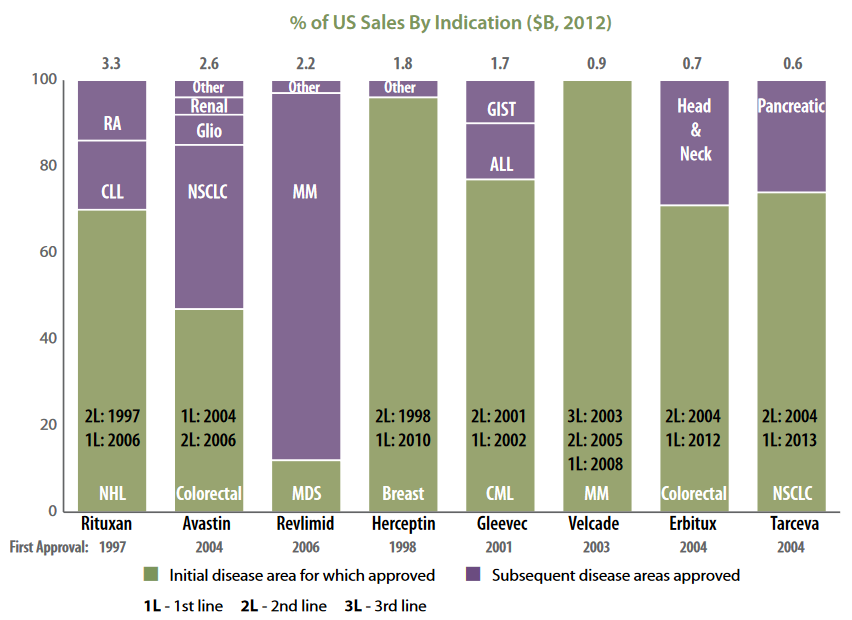

Interestingly, early indicators of product-market fit could be a bit “off”. That is, an approved drug could produce suboptimal revenue for its initial indication compared to its subsequent indication(s), as demonstrated by the sales after label expansion (ref). This is because new drugs tend to be approved for refractory indications at first, and other indications could share underlying mechanisms driving pathology. Label expansion can come in many forms, such as earlier line of therapy, different segments of patient population, or new diseases.

Source: Skvarka and Farkas 2013

Ideal characteristics of a promising biotech business

Founders building companies with drug discovery engines need to kill four major risks and advance their platform, pipeline, and partnerships (the 3 Ps). To create durable competitive advantages, startups can leverage algorithms, automation, and arbitrage (the 3 As). This is the crux of my forthcoming investment thesis.

To build and advance a robust platform, pipeline, and partnerships, founders need to have consensus-driven execution and opportunistic dealmaking skills. With a strong leadership team and advisory board, all of whom must each have outlier value-add, the founder can make the best decisions to drive forth the company and make meaningful progress. Additionally, the founder must leap at the opportunity to secure a valuable deal, whether it is landing a strategic investor, forming a favorable partnership, or poaching a talented individual. These opportunities may not be readily available, so the founder must be ready to aggressively arrange deals when the time is appropriate. This means being biased towards action.

Algorithms, automation, and arbitrage are important techniques to be highly efficient and create durable competitive advantages. These are responsible for growing the business moat and making the company into a very attractive opportunity for investors. They can take many forms, such as software for predicting molecular structures or phenotypic effects, genetically-encoded tools to enable biological programming, instrumentation for highly-parallelized screens, services that are higher quality, faster, and/or lower costs, or talented technical teams in low cost-of-living regions.

Thank you for reading, and please feel free to reach out and share your thoughts and comments! I am actively building and refining my investment thesis and would love to discuss it!

Author information

Ergo Bio closely follows innovation in the biotechnology space and evaluates interesting drugs and deals. It is run by Vandon T Duong (LinkedIn), feel free to connect! I am a biotech enthusiast and a molecular engineer by training. I am also an avid consumer of news and research around precision medicine.

Apply to join our investment syndicate and help support incredible founders and their startups! Read our related notes about community building in biotech venture, biotech venture models, and due diligence in biotech investments. We will make a societal difference by syndicating high-conviction investments in impactful startups and supporting their incredible founders!